- For those experienced with education law, the Title IX and due process violations will really jump out of the timeline even when I’m not immediately highlighting them. And for other readers, the following two-page factsheet from the Department of Ed provides a decent overview of how schools are supposed to respond to sexual misconduct reports:

https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/title-ix-rights-201104.pdf

The only material correction to that fact sheet is that the mandate for a school to investigate and act “even if a student… does not want to file a complaint” is a little more complicated than that, and some courts have ruled that pursuing investigation without permission from the complainant can constitute “deliberate indifference” if doing so harms the complainant. But we’ll go into the legal claims later. - Complainant: a student or employee who reported misconduct and/or is alleged to be the victim of misconduct.

Respondent: a student or employee who has been accused of committing misconduct. - OSU, like many universities, has a separate sexual misconduct investigation procedure for employees and students, and student complainants and respondents are generally granted more rights than employees (like the right to file appeals or cross-examine each other’s testimony).

This is the policy OIE used for all incidents occuring before 8/14/2020: - These procedures involve the Title IX office collecting evidence, then issuing a “finding of responsibility” (a guilty or not guilty verdict), then passing the report off to a different department for sanctioning (punishment, such as firing or suspension).

- OSU, like many universities, claims in their policies to offer “informal resolution.” That means that if all parties agree, the process above can be skipped, and the complainant and respondent can negotiate outcomes like apology letters or compensation instead of just damaging the respondent’s educational or professional attainment (e.g. expulsion/termination).

- While “sex discrimination” may suggest something more overt colloquially (e.g. “we’re not hiring you because you’re a woman”), this phrase refers to a broader set of statements, actions, and even inactions in the legal context. For example, a student stalking his ex-girlfriend or an institution shredding a rape victim’s report could both be considered “discrimination on the basis of sex” in a court of law.

“Sexual harrassment” can similarly refer to a wider umbrella of conduct in the Title IX context, and includes dating violence, sexual assault, and stalking – not just inappropriate comments and touches.

While still nursing her torn MCL at her work desk, Ms. Doe called the Columbus police department to file a report. The dispatcher informed her that because she was located on campus, she had to file a report with OSU’s Department of Public Safety (“OSUPD”) instead. After calling OSUPD, the dispatcher there insisted that she had to disclose Mr. Hassan’s name in order to file the report, and both interviewing officers assured Ms. Doe that word of the incident would not be forwarded to Human Resources. Already, Ms. Doe was lied to by multiple University representatives.

Ms. Doe reminded both officers not to close the report until she could follow up with documentation of her injuries, whereas Mr. Hassan came to the station that night to submit photos of his injuries.

University staff used the unfinished police report draft to generate a “Title IX Report,” and completely redacted Ms. Doe’s statements to the responding officer, so that only Mr. Hassan’s story remained to match the incomplete photo record. The Office of Institutional Equity (“OIE”) received this Title IX Report, and immediately launched an “employee” investigation into the victim who had filed the police report instead of her attacker, biasing the investigation from its onset.

Mr. Allan Williams, OIE’s assigned investigator, interviewed Mr. Hassan twice. Mr. Hassan requested an informal resolution, yet the investigator urged him to agree to formal charges against Ms. Doe (as Mr. Hassan later testified) before reporting back that the formal investigation would be moving forward anyway without the parties’ consent.

He also interviewed Ms. Doe’s supervisor [Witness 1], and after inquiring about hearsay, asked if they shared Mr. Hassan’s opinion that Ms. Doe appeared mentally unstable (and they did not share this opinion).

Here, we see the first signs that Ms. Doe was denied the presumption of innocence and open inquiry, as the investigator began building a punitive case against the victim who’d filed the report before even speaking to her.

The investigator finally emailed Ms. Doe to schedule a meeting. Despite Ms. Doe’s obvious confusion, he refused to explain that she was the respondent in an investigation, let alone the relevant policies or circumstances. He also did not provide Ms. Doe with OIE’s Investigation Resolution Standards in advance. The grievance procedures were not available on OSU’s website in compliance with Title IX— the only mention of their existence was made in Sexual Misconduct Policy 1.15, and the appropriate link was broken. Ms. Doe was denied the chance to adequately prepare for this interview, the only primary fact-finding interview she was allowed during the employee investigation.

During the interview, Ms. Doe also requested an informal resolution. She further requested the opportunity to send a written statement for more weighted consideration, since her verbal testimony was unprepared and scattered. Mr. Williams agreed to the latter.

Ms. Doe emailed the investigator a Buckeyebox link containing the complete police report (including injury documentation), a written statement thoroughly detailing the events of March 23rd, and photos and videos establishing Mr. Hassan’s history of relationship violence and kidnapping. The investigator did not save any of the evidence Ms. Doe sent him, or even view some of the files, as seen in a BuckeyeBox file audit.

OIE added Mr. Hassan as a co-respondent near this time, but refused to admit their mistake and retract the charges against Ms. Doe. The parties were each labeled dual complainants and respondents in a consolidated formal investigation, a decision made without the consent of either “complainant” and which Mr. Williams claimed was insisted on by his supervisors.

The investigator interviewed Mr. Hassan for a third time, providing him the opportunity to “cross-examine” Ms. Doe’s testimony without allowing her the same opportunity.

Ms. Doe and Mr. Hassan returned to the workplace, and resumed an on-and-off relationship until December 2020. This was in part facilitated by a power imbalance, as they had shared interests in ending the pending investigations, and only Mr. Hassan could afford a lawyer at this time.

Mr. Hassan’s physical abuse, sexual harassment, and witness intimidation escalated at home and on campus. The University had never issued a no-contact order, had actual knowledge of at least one major conflict after the respondents had returned to work together, and did nothing to remedy this hostile environment.

The investigator sent the Summary of Evidence (interview notes) for the respondents to correct. Since the investigator had only glimpsed at Ms. Doe’s evidence files only once or twice almost two months before writing this Summary of Evidence, no unique information from them was included or relied upon– just the file descriptions that Ms. Doe had written in her email.

During a phone call with Ms. Doe, Mr. Williams assured her that OIE only saw this case as an employee matter, not a student matter, and that self-defense and other mitigating factors would be considered for both the finding of responsibility and sanctioning stages. The investigator was recorded lying to the respondent on both counts and apologizing for the applicable grievance procedure not being published. He emailed a copy to Ms. Doe for the first time shortly thereafter.

The investigator allowed the respondents to submit additional testimony after viewing the Summary of Evidence, and instructed that they could only clarify their own recorded testimony and not respond to other parties’ testimony. The investigator then approved Mr. Hassan’s response to a witness’s testimony for the record— while Ms. Doe followed instructions and was denied this opportunity.

Ms. Doe’s intended response was further constrained by Mr. Hassan coercing her to include as few “aggravating” details as possible and promising to do the same. She ultimately submitted one and a half pages total while Mr. Hassan submitted several additional pages of false testimony within a twelve-page document, biasing the report even further.

The investigator issued his final Investigative Report, rushed one day before DeVos’s Title IX regulations were set to go into effect (which does not inspire confidence that the case was given appropriate care). The report determined that both respondents were guilty of relationship violence using a two-prong test: they both were in a relationship and both experienced injury. How/why those injuries were acquired and the individual facts of the case were explicitly not considered, nor were any of the mitigating factors listed in the policy. Per OSU’s written rationale, Ms. Doe was found responsible because of OIE’s zero-tolerance policy against self-defense, not because the evidence didn’t match her story.

The respondents were terminated from their positions at the lab immediately, instead of after the appeal period had elapsed, and Ms. Doe was labeled ineligible for rehire at the University. In sanctioning as well, the individual facts of the case were explicitly not considered, nor were any of the mitigating factors listed in the policy.

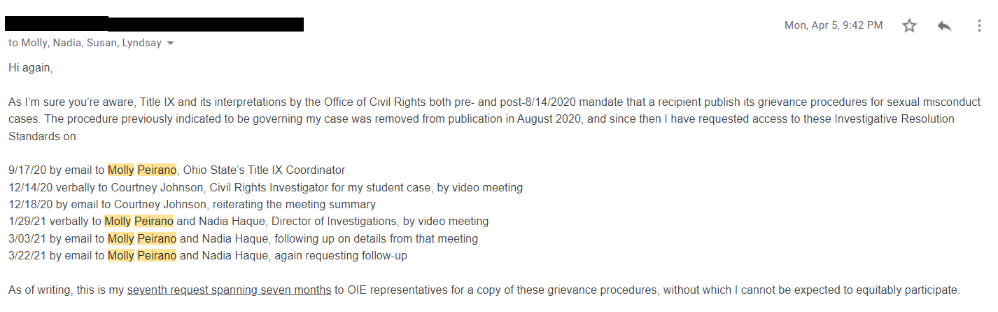

Ms. Doe’s employee email access was immediately revoked, and she lost access to all email records from August 2018 through August 2020 on her OSU email account. Her records requests for this email history were denied. In doing so the University directly and knowingly prevented her from accessing old case files and collecting additional evidence for her appeal and for the later student investigation. Because she had been accessing OIE's Investigation Resolution Standards from within an email attachment, she lost access to these as well. It took several months of constant demands for OIE to provide her with a new copy.

Ms. Doe submitted a “rebuttal” to OIE— a constrained appeal request allowed to employee respondents that OSU would have the power to reject or approve on a whim. Mr. Hassan also submitted a rebuttal near this time. Both argued in their rebuttals that it was improper to have been given the lesser rights of employee respondents instead of student respondents, that this investigation resulted in erroneous outcomes, and that they wanted the termination decisions to be overturned.

OIE launched another investigation without warning, this time attacking Ms. Doe’s and Mr. Hassan’s student statuses in a “double jeopardy” for the same March 23rd event. OIE again consolidated their cases into the same investigation as dual complainants and respondents, to be governed by the University’s pre-8/14/2020 “old” policies. This was despite the fact that:

- Ms. Doe had dropped her previously scheduled Autumn classes immediately after her termination (a harm in and of itself). This ‘student investigation’ was drawn up months later when she was not an enrolled student or conducting any business on campus where she could be a hypothetical danger.

- As mentioned, Allan Williams had previously told Ms. Doe that because the incident occurred in the workplace, OIE considered it an employment matter and not a student matter.

The student case investigator (Courtney Johnson), the Director of Investigations (Nadia Haque), and the Title IX Coordinator (Molly Peirano) repeatedly denied the respondents’ requests for informal resolution, and communicated (in writing) that OIE’s internal policy made it conditional on both respondents confessing responsibility and accepting any sanctions that OSU saw fit.

Coercing students into an imitation plea-bargaining agreement is another Title IX violation— it fundamentally violates their rights as a respondent, precludes the restorative, flexible, and nonpunitive aims of informal resolution, and subverts the “free and voluntary consent” required by the Department of Education.

The University’s Director of Affirmative Action and EEO, Terra Metzger, issued back-to-back determinations regarding the respondents’ rebuttals from August. It was determined that Mr. Hassan could appeal the employment decision using the more “fair” student investigation, but Ms. Doe could not. Even if she were found innocent by that investigation.

This is an outrageous disregard for due process standards that parties should have equal opportunities to appeal.

Ms. Doe attended a video call with the Director of Investigations and the Title IX Coordinator. During that meeting, the University’s Title IX Coordinator admitted that OIE doesn’t consider self-defense because investigating is too difficult, and that their office now automatically finds victims of relationship violence equally responsible. The origin and substance of this policy fundamentally subverts their federally mandated duty to investigate each case brought before them, and this admission decimates the validity of the University’s employee investigation.

The process of answering the respondents’ emailed questions and scheduling the hearing was subject to months of constant, unexplained delays by OIE, which they are legally required to keep respondents abreast of.

Courtney Johnson notified Ms. Doe of OIE’s decision to steamroll ahead with formal charges against her. Since OIE again refused to allow any nonpunitive informal resolution, Ms. Doe was forced to submit evidence and testimony adversarial to Mr. Hassan in order to defend her innocence.

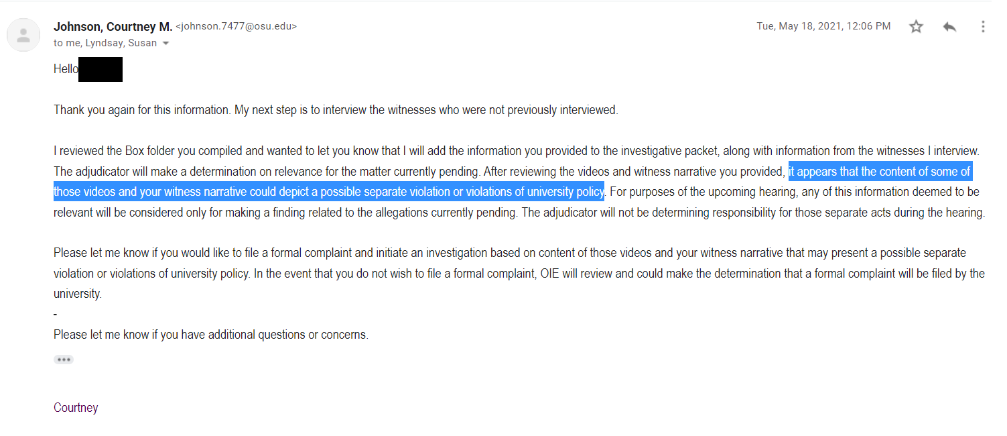

Courtney Johnson responded to Ms. Doe’s evidence submissions with written confirmation that Mr. Hassan’s violence on other dates appeared to constitute additional violations of University policy. But when Ms. Doe requested that OIE not investigate these incidents as well, her request was honored this time. This stands in contrast to the University’s previous decisions to charge Ms. Doe against the wishes of Mr. Hassan as a complainant.

Courtney Johnson compiled all of the evidence OIE had collected to use against the respondents into a “Hearing Packet” visible to all parties in BuckeyeBox.

The packet showed that OIE had resubmitted the incomplete draft of the police report with only Mr. Hassan’s injuries, the Title IX report with only Mr. Hassan’s testimony, the investigative report with Mr. Hassan’s three fact-finding interviews vs. Ms. Doe’s one and Mr. Hassan’s policy-bending corrections to other witnesses vs. Ms. Doe’s zero all as evidence to initiate the student investigation. This immediately, structurally precluded any opportunity for a fair and unbiased process the second time either.

Brett Sokolow, the president of ATIXA, was hired to act as a third-party adjudicator.

Upon meeting with Ms. Doe, Mr. Sokolow confirmed that his interpretation of the written policy did not preclude self-defense.

Mr. Sokolow also revealed that OIE was not providing him material support in his investigation. OIE failed to find and send him a building plan of the Biomedical Research Tower where the 3/23 incident took place, and Ms. Doe had to provide these herself.

A virtual hearing was conducted for the student case. Mr. Hassan and his counsel conducted themselves poorly, interrupting the hearing at one point to accuse Ms. Doe of texting testimony to a witness before being proven wrong.

The third-party adjudicator issued his report, determining that both respondents were not guilty of relationship violence. Notably, the report characterized Ms. Doe’s actions to extricate herself as being in good faith, and justified Mr. Hassan’s unlawful imprisonment as acceptable as long as Mr. Hassan believed that Ms. Doe was a danger to herself. There didn’t need to be supporting evidence that this belief was rational – Mr. Hassan just had to claim he believed it.

Mr. Sokolow’s report was subject to review and approval by University administrators before it was released, and that review processes and the individuals involved were not disclosed in either the public grievance procedures or by Ms. Haque when Ms. Doe inquired. This lack of transparency, OIE’s previously articulated policy of issuing equivalent findings for both parties, and the contradiction between Mr. Sokolow’s condemnations of Mr. Hassan’s behavior and his final determination all raise doubts as to whether the third-party adjudicator was truly given judicial autonomy.

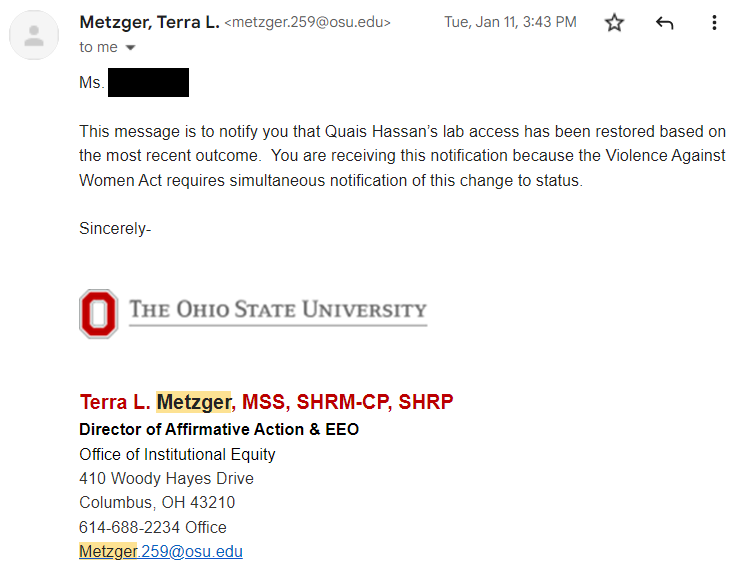

Ms. Metzger notified Ms. Doe that Mr. Hassan’s lab access has been restored, citing the Violence Against Women Act without irony. Ms. Doe is still blacklisted from employment at OSU.

I will be attaching a longer document later that breaks down my legal claims in much more detail, linking specific statutes to specific sections of the timeline and case law. But this is the condensed list of my legal claims, with a few extra points excerpted that aren’t as obvious from the timeline above. OSU violated almost every recognized facet of Title IX law– within the direct statutes, Department of Education guidelines, and due process established by case law– as well as other civil rights laws parallel to each claim.

- The Ohio State University’s actions demonstrate a pattern of negligence (including negligent retention) and deliberate indifference toward responsibilities under Title IX, perpetuating further due process violations under other laws and damages.

- The OCR lists a 60-day guideline for investigations to minimize the impact to students and employees, with exceptions for clearly-communicated just cause, and University policy parrots this. Between the initiation of the employee investigation on March 24th, 2020, and the conclusion of the student investigation on October 27th, 2021, the University held investigations over Ms. Doe’s head for 582 days. The Sixth Circuit has previously found 240 days to be extreme.

- OIE has been understaffed for years, which is verifiable through public employment records widely reported by other survivors and former staff members.

- After the University wiped Ms. Doe’s email history on August 14th, 2020, she had to contact OIE seven times over the span of seven months before they sent her a copy of the Investigative Resolution Standards again. For more than 582 days, OIE did not have their active grievance procedures (for all assaults that occurred prior to 8/14/2020) publicly available, one of a Title IX office’s central responsibilities.

- Ohio State employs a single Title IX coordinator to oversee policy review and compliance for disciplinary cases arising from over 100,000 students, staff, and recent alumni. For most of the duration of Ms. Doe’s case, this role was taken by Molly Peirano, who was concurrently a PhD student studying for her candidacy exam, balancing another position, suffering from a concussion, and overwhelmed, according to her social media. It can be assumed that this affected her ability to perform the role of Title IX coordinator, as seen in early 2021 when Ms. Peirano took multiple months to answer Ms. Doe’s emailed questions.

- The Ohio State University and its agents violated Ohio law, Title VII, Title IX, the ADA, and the 14th amendment via wrongful termination and other retaliation against legally protected activities.

- Self-defense, when used under true duress and not excessively, is universally considered to be a civil right and protected opposition activity. Filing a police report and/or reporting an incident within the employer’s internal channels are protected participation activities.

- The Ohio State University and its agents violated Ohio Law, Title VII, Title IX, and OSHA by both creating a hostile environment that was severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive and failing to appropriately investigate or remedy that sexual misconduct and hostile environment.

- The Ohio State University and its agents violated Ohio law, Title VII, Title IX, the 14th Amendment (Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses), their own written policy, and contractual obligations by denying Ms. Doe procedural and substantive due process and displaying disparate treatment and favoritism toward Quais Hassan, their MD/PhD trainee.

- Multiple courts (including the Sixth Circuit), have upheld that use of the single-investigator model and denial of the opportunity to cross-examination violate due process rights under Title IX (even prior to the OCR Final Rule).

- The Ohio State University and its agents violated Title IX in particular when this lack of due process generated disproportionate and erroneous outcomes in both investigations.

- The Ohio State University and its representatives violated Ohio law, Title VII, Title IX, and the ADA by overtly discriminating on the basis of sex and disability.

- Mr. Hassan’s recorded gender-based violence and professed motivations for this a la disability discrimination speak for themselves on both fronts.

- The first male decision-maker leaned into this "crazy ex-girlfriend" narrative of Mr. Hassan's, urging him to press charges against Ms. Doe and interviewing witnesses about Ms. Doe's mental health while throwing away the evidence she sent.

- The second male decision-maker’s determination posits that despite Ms. Doe showing no signs of crisis, because she had previously disclosed her mental health disability (clinical depression) to Mr. Hassan, it would have been sufficiently reasonable for Mr. Hassan to assume that she was in crisis and ignore her pleas to leave.

It is discriminatory and dangerous precedent to authorize that students or employees may unlawfully restrain another to the point of harm, solely because the victim has a pre-existing disability. This specific circumstance has even been the subject of a recent Title IX enforcement initiative by the OCR, as they define unwarranted restraint to be a violation of a student’s civil rights. - The Ohio State University did not uphold contractual obligations or generally act with honesty, fundamental fairness, or good faith toward Ms. Doe or the public. Their policies may even have a disparate impact on women.

- OIE’s zero-tolerance policy toward self-defense is purportedly rigid, yet not disclosed to the public or to the contracted students and staff in any of the relevant policy documents. Indeed, this hidden active policy contradicts the written policy, as the “mitigating factors” in the Investigative Resolution Standards fully encompass the elements of self-defense.

- OIE, OSUPD, and campus newsletters had also directly advertised self-defense courses specifically for women for years prior to this incident, since they know that women are more likely to need to use self-defense. The University effectively entrapped Ms. Doe through constant advertising that she’d be supported and protected if she needed to use self-defense and/or report an assault. OSU’s expectation that victims of relationship violence should stand still was not at all apparent. Knowingly and deceptively modifying the terms of the disciplinary policy and associated contract with Ms. Doe before retaliating against her for allegedly breaking those hidden terms constitutes negligent (if not fraudulent) misrepresentation and breach of contract by the University, not her.